Collecting Ourselves

Objects, Identity, Memory, Furniture

Furniture, apart from its immediate utility, visual and tactile qualities, also supports the immaterial stuff of life. In furniture we collect desire and longing, memories of loved ones, hope for future recognition, and tangled clusters of emotions about times and persons now past.

Onto furniture’s fixed, external surfaces we project our own ephemeral, internal world.

Our corporeal experience of home depends on this receptive, receptacle-quality of furniture. Within the carapace of the house, furniture enfolds our bodies and our selves .

Collecting Ourselves isn’t only about containing a plurality of possessions—it’s equally about the condensing, contemplating, sharing,

arranging, and gifting of these things.

Ark and scaffold

for your tokens,

talismans,

treasure maps

A place for turning

what’s inside

out

“As we all know a Dalek (pronounced /ˈdɑːlɛk/ ) is a member of a race of hostile alien machine-organisms which appeared in . . . Doctor Who from 1963). We have named our Dalek as D1, only because it’s dee one in our house. . . . The ‘novelty’ for our visitors has worn off and D1 is now accepted as part of the furniture. This is probably because D1 has been in residence for some months now. . . . My wife has found one practical use, unbeknown to me. She is using the bottom quarter of the space as storage for her on again, off again knitting. . . . The major comments from family/friends continue to be that D1 is different . . . and beautifully made.”

Ark IV, 2018, displaying possessions of the trial participant quoted above.

By moving the piece away from the wall, we get both spatial prominence and contrast with background — a discrete form,

an interior landmark.

Ark V

My aim is to design furniture that induces vortices, to stall the strolling ogler, creating an eddy in time with a set of meaningful possessions.

Ark I

As in the metaphoric expression “to shoulder your burdens,” these arks hew to the human body.

Across diverse cultures, people suspend bags or baskets from their shoulders. Both the shoulder pole and the hobo’s bindle stick unite a minimal structure, a bundle of possessions, and the human frame.

Here, the table with a bag slung underneath marries furniture with a person and the things they carry.

Man carrying goods on a pole cross his shoulder, 1936. Tea plantation, Assam, India.

Photo credit: Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf. Source: Archives and Special Collections, SOAS, Univ. of London, accessed 9 March, 2019, https://digital.soas.ac.uk/LOADI05069/00001.

Recruits … hold their sea bags during pick up. … Drill instructors ensure that the recruits fill their bags with the appropriate items and that extra gear is emptied into the recruit’s footlocker.

Photo credit: Cpl. Angelica I. Annastas. Source: Marine Corps Recruit Depot/ Western Recruiting Region,24 July, 2017, accessed 9 March, 2019, https://www.mcrdsd.marines.mil/News/Photos/igphoto/2001782312/.

WWII duffel bag belonging to US Army Capt. J.G. Mitnick, 1944.

Source: "US Army duffel bag used by a soldier," United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, accessed 9 March, 2019, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn518201.

Bag from Ark I, using selective colours and fabric to signify an individual’s belongings.

Ark I and Ark II variations, with hanging bags.

Ark III, with freestanding bag.

Ark VI

Storage boxes claim homogeneous space, their flat bottoms mating with planar floors and shelving, their lids enclosing, thwarting one’s senses. In contrast, baskets support nomadic movement, gathering and emptying; culturally distinct in materials and forms, a basket’s shape can be tuned to tie the burden closely to the body.

Baskets are fibre prostheses mediating between a people and their world.

Two women carrying a basket filled with straw. Nagaland culture, 1936.

Photo credit: Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf. Source: "SOAS Digital Collections," School of Oriental and African Studies, Univ. of London,accessed 9 March, 2019, https://digital.soas.ac.uk/LOADI05105/00001.

“The body … does not memorize the past, it enacts the past, bringing it back to life. What is 'learned by body' is not something that one has, like knowledge that can be brandished, but something that one is. This is particularly clear in non-literate societies, where inherited knowledge can only survive in the incorporated state. It is never detached from the body that bears it. … Body hexis speaks directly to the motor function, in the form of a pattern of postures that is both individual and systematic, being bound up with a whole system of objects, and charged with a host of special meanings and values.”

Pierre Bourdieu, The Logic of Practice, trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1990), 73-74.

Native American women making baskets, Olympic Peninsula, 1926.

Source: University of Washington, University Libraries, accessed 9 March, 2019, https://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/digital/collection/loc/id/98/rec/35.

The materiality and form of traditional baskets are contingent on the producing culture, their local ecology, and their specific needs; basket-makers weave pliable plant fibres, like the roots of marsh grasses for native Californians, birch tree roots in the case of the Sami culture, or bamboo cane, rattan and palm for many Asian traditions. When and where to harvest material, how to scrape and dry, how to prevent rot, how to soak and make flexible again — this is a fraction of the knowledge that traditional basket weavers engage before they begin shaping a form.

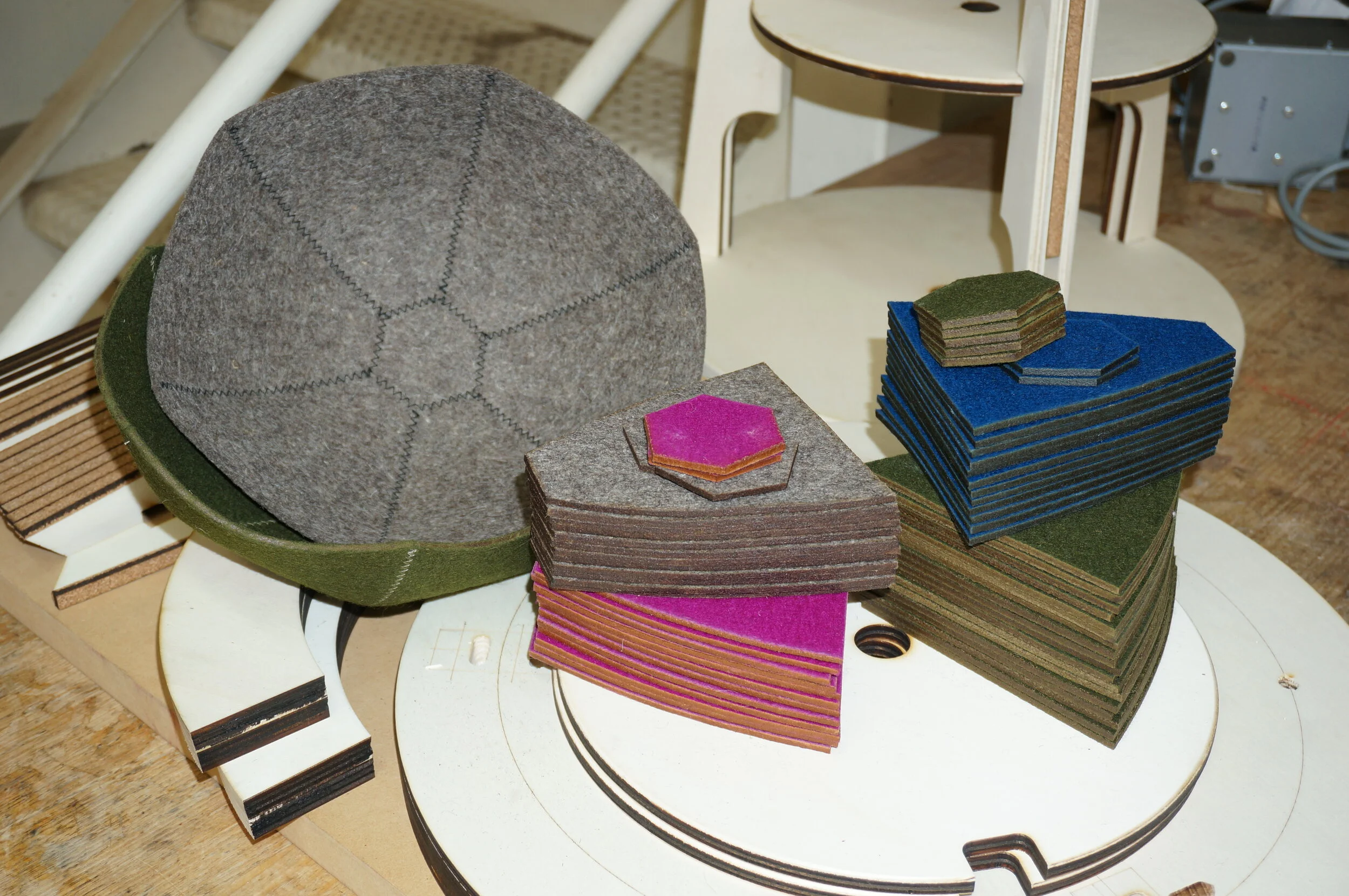

Ark VI, getting dressed

Why no doors or drawers? These components add weight and bulk, which makes moving the furniture more cumbersome, and they force cabinetry into a single useful orientation, back against a wall, pushing cherished contents to the margins. Furthermore, concealing treasures undercuts the repeated encounters with the artefacts that can bolster individual, family, and cultural identity. This highlights a potential paradox of storage — an archive may conserve physical substances, but total enclosure eclipses the vibrant storytelling that might accompany one’s things, handing posterity a capsule of pristine objects from which the intangible adornment of personal meaning has been stripped. Consequently, in “economies of abundance,” the dead leave behind cupboards, drawers, and boxes of possessions for receiving generations to puzzle over or discard, the residue of unrecounted life experiences now forever lost to time.

Possessions and Time

“We should dismiss the cliché that man survives through his possessions. Creating a safe haven has really nothing to do with securing immortality, perpetuity or some sort of afterlife by way of a mirror–object . . . but is a far more complex game which involves the 'recycling' of birth and death within an object‑system. What man wants from objects is not the assurance that he can somehow outlive himself, but the sense that from now on he can live out his life uninterruptedly and in a cyclical mode, and thereby symbolically transcend the realities of an existence before whose irreversibility and contingency he remains powerless.”

Jean Baudrillard, "The System of Collecting," in The Cultures of Collecting, ed. John Elsner and Roger Cardinal (London: Reaktion Books, 1994), 17.

“For many Australian Aboriginal communities, linear time is perceived to have a depth of only a generation or two. This linear time exists along with what I call ‘temporal wave time’. In temporal wave time all events exist alongside each other on a flat temporal plain, like the face of a wave that moves forward, capturing all history as it progresses.”

Rob Paton, "The Mutability of Time and Space as a Means of Healing History in an Australian Aboriginal Community," in Long History, Deep Time: Deepening Histories of Place, ed. Ann McGrath and Mary Anne Jebb(Canberra, A.C.T: ANU Press, 2015), 71.

A revolving round shelf challenges the notion of beginning and end, allowing artefacts to appear coeval without privileging a sequential reading.